Apple’s iPhone is not a monopoly like Windows was a monopoly. This morning in federal court, the attorneys general of sixteen states, the District of Columbia, and the United States Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Apple. According to the lawsuit, the business maintains a stranglehold in the market for high-end smartphones by employing a number of illegal strategies.

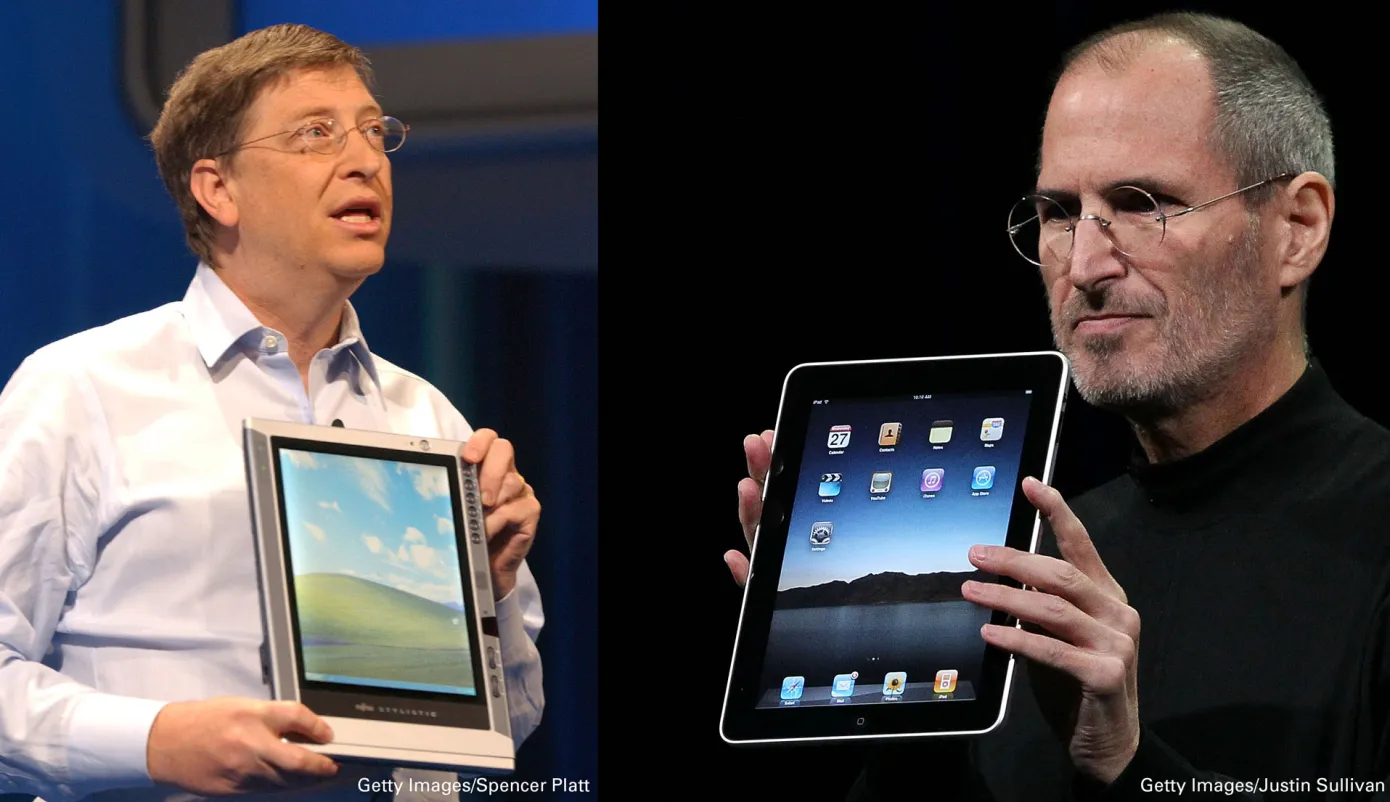

Disregarding the specifics of those strategies and their legality (you can read the full lawsuit here if you’re interested), there are many similarities between this case and the DOJ’s 1990s antitrust action against Microsoft, which I wrote about for Directions on Microsoft from 2000 to 2010. “The landmark Microsoft case held a monopolist liable under the antitrust laws for leveraging its market position to undermine technologies that would have made it easier for users to choose different computer operating systems,” Attorney General Merrick Garland said, pointing out the similarities. According to the complaint filed today, Apple has adopted several of Microsoft’s strategies.

One significant distinction exists between the instances, though: Microsoft had an unquestionable monopoly on the pertinent personal computer operating system industry. The extent of Apple’s monopoly is not nearly as obvious.

In his press conference, Garland also mentioned that having a monopoly is not against the law. but, it is unlawful to employ certain strategies to uphold or extend that monopoly; but, in order to establish this, you must show that the defendant has enough market power to drive out rivals.

The market share of Microsoft Windows was well over 90% in the relevant personal computer operating system market. In fact, it dominated the pre-smartphone period so much that, according to a 2000 estimate from Goldman Sachs, 97% of all computing devices were running Microsoft operating systems.

The DOJ’s antitrust case against Microsoft resulted in a mixed bag of wins and losses. While many of the penalties, such as Microsoft’s split into two companies, were overturned on appeal, the case’s factual conclusions unequivocally proved Microsoft had monopolistic power. This opened the door for several further private cases, the most of which Microsoft settled.

Apple has a far smaller market share when looking only at numbers.

According to the DOJ’s lawsuit, Apple has a greater than 70% market share of smartphones in the United States when revenue is taken into account. This is not the same as gauging by units shipped; in that case, Apple’s share is closer to 64% as of the final quarter of 2023, figures from Counterpoint Research show, significantly ahead of Samsung, which comes in second at 18%. The DOJ counters that other criteria, such as the majority of young users’ preference for iPhones over Samsung phones using Google’s Android operating system, demonstrate the iPhone’s superiority. Households with a higher demography also favour the iPhone.

The government also claims that the U.S. market is significant because, among other reasons, any new entrants must abide by U.S. telecommunications rules and the majority of customers buy smartphones through carriers. This debate is crucial as Apple’s worldwide market share is substantially smaller—just 23%, compared to 16% for Samsung in second place. The first place is titled “Others,” and it is primarily occupied by inexpensive Android phones. It is evident that the global market is still fragmented, which alters the competitive landscape. For example, developers are highly motivated to create apps for Android. Compare this to Microsoft’s worldwide market domination, which at the time had very few strong competitors.

Page 66 of the DOJ’s lawsuit contains the crucial passage, “Apple has monopoly power in the smartphone and performance smartphone markets.” The crux of the issue revolves around entry obstacles.

First, according to the DOJ, the majority of consumers are upgrading when they purchase a new smartphone and are more likely to select an iPhone since the majority of those users already own one. The DOJ asserts that Apple has erected numerous artificial barriers that make it difficult for users to switch, like the distinction between blue and green messaging bubbles for users of iPhones and Android phones and the purported restriction of third-party cross-platform video apps’ functionality in favour of FaceTime, which is exclusive to Apple devices. If consumers decide to move, there are expenses and difficulties to consider, such acquiring new apps, learning a new UI, moving data, and so forth.

Second, the DOJ lists numerous technical obstacles to entrance, including the need to secure distribution agreements, build complex hardware and software, and purchase pricey components. Numerous indirect indicators also exist, such as Apple’s substantial and steady profit margins on iPhone sales.

A court hearing the case might find these arguments persuasive. Apple can counter that product integration and differentiation are not the same as eliminating competition when it comes to entry barriers. Customers pick and continue to choose a fully integrated platform with built-in programmes for specific capabilities like web surfing and videoconferencing because it is straightforward and convenient, not because they would like to migrate to Android and are prevented from doing so by fictitious impediments.

In the second scenario, Apple may legitimately question why it is being penalised now for taking the required steps to establish a lead, pointing to the significant expenditures it has made over the last 15 years to create these supply chains and connections with carriers and developers.

In the tech industry, antitrust charges frequently follow this pattern. An innovator becomes successful by using a combination of cunning business strategies, hard labour, and good fortune. They use network effects to their advantage to establish an impregnable lead. Rivals voice grievances. The government steps in. When a dominating player stalls out for an extended period of time, new competitors find a way to enter the market. This is similar to what happened to Microsoft in the 2000s when Apple and Google launched their smartphone operating systems, significantly decreasing the relevance of desktop PCs and Windows.

The cycle then resumes at that point.